Foreword

As part of its commitment to research-based standards development, each of the past several years, the Council for Interior Design Accreditation (CIDA) has scanned the environment, looking for data, trends, and other information as to what designers - and therefore students - will need to know to be prepared and successful in practice. Scans like these of economic, demographic, environmental, and technological trends are invaluable for charting the future in increasingly uncertain times.

But so too is looking deeply into the interior design profession itself, to what it might become over the coming years. That was the objective of this Future Vision 2020-21 - a thoughtful look at what interior design practitioners, educators, and allies think, feel, and believe about the profession and what that might mean for the early years of the field’s second century.

The pandemic disruption of 2020 led to a much-extended process - from an originally-scheduled weekend event to a 14-month investigation - enabling CIDA to cast a much wider net for input from inside, adjacent to, and outside interior design and to be more contemplative about what we heard.

CIDA intends to do two things with this report -

Use it to facilitate a more holistic review of accreditation standards, and

broadly distribute it, thus making findings available to constituents and others in the professions for use in their own strategic visioning.

“Our world has become smaller. Humanity now aspires to provide care, work, play, and live more meaningfully. As professionals, emerging or established, it is our responsibility to design environments that support this quality of life for all. This is the future of design.”

“The highest and best purpose of interior design is to create environments that strengthen the connection between people and their world and foster a true sense of belonging for everyone.”

Timeline

Scan and summit about what interior designers need to know to design for individuals, relationships, organizations, and society

2019

Survey of thought leaders in and around interior design on teh highest and best purpose of interior design.

December 2020

In-depth interviews with leaders in allied fields on the highest and best purpose of interior design

December 2020

In-depth interviews with leaders in fields that have transformed

January 2021

Session 1

What is interior design?

Facilitators: Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs and Stephanie Pace Marshall, Founding President and President Emerita, Illinois Math and Science Academy

March 2021

Session 2

Who is in our ecosystem?

Facilitators: Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs and Zach Anderson, Partner, The Converge Network

March 2021

Session 3

How does interior design move in the world?

Facilitators: Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs and Ethan Decker, Founder, Applied Brand Science

March 2021

Session 4

What does the future hold for interior design?

Facilitators: Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs and Lisa Kay Solomon, Designer in Residence, Stanford d. school

March 2021

INITIAL FINDINGS

There is a gap between interior design values and practice.

It looks like the field of interior design is on the precipice of significant change. Of course, all fields evolve over time, typically in response to external disruptions in supply, demand, workforce, and/or technology. The interior design field is no exception, evolving with ever-increasing knowledge and subsequent impact on people and the environment. The profession has progressed with accredited higher education, the NCIDQ examination and, in many cases, legal recognition to signify competency.

This next change, addressed here, will be very different. It won't be triggered by external disruption as much as evolution in what interior designers themselves have come to think, feel, and believe about the role of their profession.

“Our highest purpose, as interior designers, is to serve humanity. We are the gatekeepers of good, articulated in the environments we create.”

Categorization of thought leader responses to survey question, “What is the highest and best purpose of interior design?”

It's about the quality of life, rather than quality of space.

As part of this project, 68 thought leaders were surveyed in and around the interior design field, posing a single question. "What is the highest and best purpose of interior design?" Their answers were remarkably consistent and unambiguous. The purpose of interior design is to enhance people's experience and quality of life.

Of course, it's a reasonable leap from quality of space to quality of life. Science and the growing body of knowledge is proving the impact of space and all its attributes on the human experience. The thought leaders' responses to the survey featured 26 central ideas - 70% of which were related to end users: their experiences, quality of life, health, relationships, spirit, performance, resilience, mindset, grace, happiness, and love.

Four more central ideas were even more aspirational: humanity, inclusiveness, justice, equality. Only four central ideas in the respondent's answers were related to space - namely, comfort, functionality, life, safety, and quality.

“Interior designers have the opportunity to be the integrators for designing the future human experience.”

“The work of interior designers creates a positive impact on the world when done in a thoughtful, inclusive way. That is the highest and best purpose of design.”

The shift in designers' ambitions is consistent with changes in generational issues and perspectives.

Research suggest that today's students embody an unprecedented mix of ambition and social consciousness. Consider their real-world experiences: recession, crippling student debt, social injustice, climate change, the pandemic, and hyper-partisanship.

“Gen Z still has a lot of growing up to do. But as they continue to come of age, early signs indicate that they will grow into engaged, conscientious stewards of our world — by being socially-minded, independent thinkers, who recognize their responsibility in shaping a more equitable future for all.”

“As the baby boomer generation begins to retire, the interior design profession needs to cultivate future designers as the next advocates to demonstrate the power and impact of design”

“We must be the authors of a new narrative - one that puts the next generation first and that works to correct the damage we have done. Maybe a few hundred years in the future a mother will read to her child: ‘Once upon a time a group of designers and artists and engineers and world leaders re-imagined design and what their purpose should be …”

The current student body represents the first generation who've grown up in a ubiquitous digital world. They are more likely to be more interested in other people - such as end-users - than in technical skills, which they've seen get increasingly automated.

Not only will this reinforce the use of empathy as a primary design tool, central to human-centered design process, but the generational comfort level with technology advancements such as artificial intelligence, augmented reality, and virtual reality will provide opportunities to experience space throughout the design process and engage end-users in the process more than ever before.

The shift will likely bring a redefinition of interior design itself.

The predominant definition of interior design within the field was crafted by the Council of Interior Design Qualification, primarily to evolve and further delineate the scope of practice, and is referenced by many organizations, including CIDA.

Here is the abbreviated version. (All of the words in the next paragraph are accurate and we acknowledge the efficacy of the NCIDQ exam and the potential for interior design licensure. As times goes by, credentialing, licensure, and scope of work will evolve.)

“Interior design encompasses the analysis, planning, design, documentation, and management of interior non-structural/non-seismic construction and alteration projects in compliance with applicable building design and construction, fire, life-safety, and energy codes, standards, regulations, and guidelines for the purpose of obtaining a building permit, as allowed by law. Qualified by means of education, experience, and examination, interior designers have a moral and ethical responsibility to protect consumers and occupants through the design of code-compliant, accessible, and inclusive interior environments that address well-being, while considering the complex physical, mental, and emotional needs of people.” (Endnote 1)

“I would like to rename our profession. I don’t think it’s just about the interior, it’s about the people. So maybe we’re known as designers for humanity”

“The highest and best purpose of interior design is in enhancing the quality of life of all people. Design surrounds us in all aspects of our lives—where and how we live, work, play, heal, and learn.”

People’s well-being and needs frame a list of technical skills and tasks. The full definition spells out 10 scope of service areas (for example, project management, project goals, data collection, existing conditions evaluation) that emphasize technical and professional proficiencies.

The first Future Vision 2020-21 session hinted at where a next- generation/evolved definition might go. After two hours of discussion, a survey of session participants generated the following definition: “The specialized discipline for creating spaces and experiences that allow people, the community, and the planet to thrive.” The aspirational nature of the resulting definition was unexpectedly enlightening. While it does not exclude the technical delineation of the CIDQ definition, it transcends it, moving beyond the conventional regulatory realm to one of impact.

The evolution will likely affect the balance of necessary skills.

To better understand the educational impact of future changes in the interior design profession, we asked a group of design leaders and senior educators what interior designers need to know to design for individuals, relationships, organizations, and society at-large. They offered up 171 different skills and understandings.

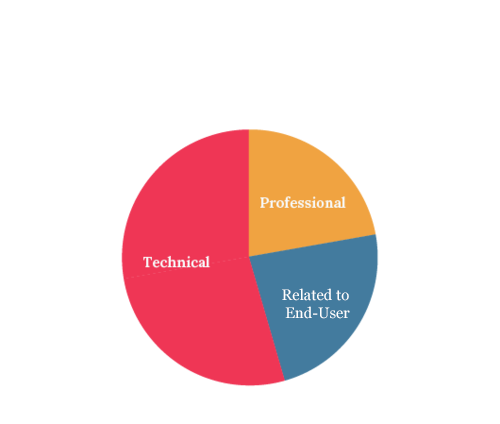

Ninety-one (53%) of the skills and understandings were technical, such as universal design, acoustics, and 3-D design composition. Thirty-seven (22%) were professional skills and understandings, such as scheduling, budgeting, and communication. The remaining 43 (25%) were skills and understandings related to end-users, such as social and cultural context, engagement, and productivity drivers, and understanding how work in the office gets done.

Before there’s an outcry: yes, there are absolutely interior designers whose practices reflect a difference balance of skills and understandings. But it’s very likely that the vast majority of the 90,000-plus working designers and design students in North America are undoubtedly working and learning this way. (endnote 2)

“The highest and best purpose of interior design is to enhance, advance, enrich, improve, and elevate the human experience in the spaces in which we live, work, play, heal, and learn.”

“Isn’t it interesting that the message from interior design is more about living systems, while the practice itself is transactional? It’s just interesting that the cobbler’s children have no shoes”

Design leader and senior educator responses to survey question, “what do interior designers need to know to design for individuals, relationships, organizations, and society at large.”

The series of shifts will likely impact CIDA standards.

The current CIDA professional Standards include 13 areas of emphasis under "Knowledge Acquisition and Application," that mirror the balance of technical and professional skills in the current interior design practice and the CIDQ definition. Of the 13, three speak directly to the essential role of end users: Global Context, Human-Centered Design, and Environmental Systems and Human Wellbeing. The remaining standards and criteria are more technical and skills-based albeit framed with regard to interior design's broader impact and value.

If the field evolves in response to the changing values, it's likely - and essential - that aspiring designers be prepared differently. We address this in more depth next.

“Design is not just about the physical space, but about all the emotional and psychological stuff that happens there.”

“We must evolve, to further focus on the people that we support. Interior design is about the people”

CIDA Professional Standards mirror the technical and professional skills necessary for practice competency. Standards 4-16.

Analysis of Findings

Closing the gap will require disrupting the ecosystem.

When confronted with a gap like the one opening between interior design values and practice, there are three options:

ONE

Ignore it and carry on with business as usual. This is likely a bad idea, as working designers and design students will become increasingly frustrated that their "why" and "how" are misaligned.

TWO

Adjust the values. This would be nearly impossible. It would mean swimming against the currents of ingrained culture, generational changes, and the emerging beliefs of the field's own leadership.

THREE

Adjust the practice. This is undoubtedly a big task, but it appears to be the field's best option.

A biographer of Andy Warhol wrote that Warhol's genius lay in how he ran to the edge, planted a flag, declared it the new middle, and watched as everyone in the art world scrambled to reorganize themselves around it. For interior design to close the gap between its values and practices, the field will have to be equally brazen.

“It’s about people, right? If we don’t get that right, if we don’t educate not just our students but the public about the true nature of interior design, we’re going to be in this loop forever”

The current ecosystem is an impediment.

In our second Future Vision 2020-21 session, participants were asked to graphically represent the current interior design ecosystem. Who are all the various actors? How do they relate to each other? At the center of nearly every drawing was the "client" (or "owner"), and inside were individuals/end users.

The resulting drawings offered no surprises. They made perfect sense, depicting both the human-centered nature of the work and the inevitable intercessory role of the "client" in many cases. In this common current construct in order to impact individuals and end users, interior designers must often serve "clients" first. Which can mean very different, if not conflicting interests guiding a project.

Again, not surprising. First, professional interior design in neither a hobby nor an act of charity. Professionals have to get paid and, in the real world, clients control the budget and finances. Second, in our economic system, all professions run on the operating system of business, which values costs, margins, return on investment (ROI), and the like. Third, even if the operating system is flawed and fails more often than it should, it is the incumbent and extraordinarily hard to change.

The onus for change will fall to the interior design profession.

In a perfect world, the other actors in the current ecosystem would invite interior design to infuse new values into their shared work, and collaborate with interior design to develop and support new practices. While this may ultimately occur, organic change often occurs slowly. Other actors in the current ecosystem - developers, architects, other allied professionals, and clients are entrenched as interior design in the current ways of conducting business. Reconfiguring legacy, industry-wide practices and culture, familiar relationships and ways of conducting business would be a monumental, shared commitment and unlikely to be of equal interest to everyone at the table.

That doesn't mean change is not possible. The field of healthcare is experiencing a similar transition. Healthcare practice is moving more and more towards patient experience and quality of life - and away from the traditional, physician-driven mechanistic values of disease and cure. This transition is being led by nurses, who, like interior designers, place people at the center of their ecosystem. With increased recognition of the impact of human experience on health and wellness, nurses, as a fundamental and consistent interface with patients, are becoming central figures in healthcare, running hospital systems and shaping public policy.

“There are transformative changes occurring in healthcare for which nurses, because of their role, their education, and the respect they have earned, are well positioned to contribute to and lead. To be a major player in shaping these changes, nurses must understand the factors driving the change, the mandates for practice change, and the competencies (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) that will be needed for personal and systemwide success.”

If the nursing profession can do it, so can interior design. Both fields face similar challenges. Both are historically and remain female-dominated professions in a culture that places more value on male contributions. And both have matured in the shadow of a highly technical, high-status field.

“Often, the world of interiors is painted as a traditionally feminine endeavor that may be deemed frivolous or decorative, and the heroic, architecturally masculine mindset of injecting rigor, practicality, and logic has been known to take over and render a space cold or sterile. Interior design can have a profound effect on people’s lives because we as designers are empowered to use a design vocabulary that is traditionally restricted for the architectural community at large.”

Such a change must challenge the most basic assumptions.

If the ecosystem is to be reorganized around end-user experiences and quality of life, all actors in the built environment, will have to re-examine their foundational beliefs. The interior design profession is no exception.

For example, interior design and related construction services are typically funded by capital budgets. however, if interior design and its impact were widely understood as a way to improve:

employee experiences, it could be funded by human resources.

customer experience, it could be funded by sales.

patient quality of life, it could be funded by health insurance.

student outcomes, it could be funded by school operations budgets.

There are undoubtedly a dozen similar assumptions buried within current partnering and funding practices that should be more closely examined. Challenging those assumptions, rather than the practices they engender, would likely open up new possibilities for the whole ecosystem.

The secret weapon of disruption may be end-users themselves.

Of all the actors in the current ecosystem, none engages end-users more than interior designers. Changing the form of that engagement could help transform the ecosystem itself. End-users are sources of immense data. What happens in the space? What could happen in the space? What is needed in the space? The list goes on. Bringing users more fully into the process as true collaborators offers new opportunities for disruption.

The interior designer has a unique role. Interior designers often lead the visioning, programming, and goal setting. They are the primary professional that advocates for the human being in the built environment. The interior designer has an outstanding platform from which to fundamentally shift the design process toward metrics around human performance, health, and wellness. Furthermore, interior designers play a critical role in defining, measuring, and documenting those metrics in a way that equates to ROI and other dominant, system-driven values.

“We’re operating in a larger transactional setting, which means that the project has to come to an end. We didn’t make it that way. I think designers would be predisposed to make sure it continues to work for end users forever and ever and ever. But in a transactional universe, we get to the end because the checks stopped coming or the Gantt chart has hit the right edge of the paper.”

In our third Future Vision 2020-21 session, we asked participants to think about interior design as a brand building a stronger identity. As such, we posed a series of either/or questions. Note the consistency in the group's answers.

Q: Should interior designers be thought-leaders or crowd-sourcers?

A: They should be thought leaders on

engaging end-users.

Q: Should interior designers democratize or premiumize?

A: Both - they should democratize by pushing power down to end-users and premiumizing by starting with organizations that “get it.”

Q: Should interior design narrow its scope or zoom out to think about the whole ecosystem?

A: The field should think about a whole ecosystem focused on end-users.

Q: Should interior design be about values or outcomes?

A: The field should be about values of end-users and very different outcomes than we have now.

Q: Should interior design narrow its focus or widen its aperture?

A: The field should narrow its focus to end-users and widen its aperture to include all end-users.

These shifts would radically change dynamics within the current ecosystem. Consider how public referenda changed politics and government in California and the UK. Shifting from a representative model, wherein interior designers represent the interests of end-users, to a direct participation model, wherein end-users represent themselves, would be a seismic change. And it would require all other actors in the current system to adjust how they work as well.

This would require going well beyond empathy.

Some years ago, two historians wrote an influential piece about the traditions of philanthropy. (endnote 3) The first tradition, they said, is the most straightforward: philanthropy as relief or, as we more commonly know it, "give a man a fish." The second tradition is philanthropy as improvement or "teach a man to fish." The third is philanthropy as social reform or changing the system that made it difficult for the man to have a fish in the first place. They closed the piece by advocating for a new, fourth tradition: empowering the man to make changes himself in the inequitable system.

Engaging end-users as true collaborators would be akin to this fourth tradition. It would require interior designers to marry expertise in space with expertise in empowering end-users. And this means: moving beyond empathy, according to Bobby Martin, Jr., a visual designer who Fast Company called one of the most creative people in business. (endnote 4)

"For Martin, that's a recognition that one of the biggest design tropes of the past decade - design thinking centered around ‘empathy’ - is a lie,” Fast Company wrote. “A lot of companies based their design ethos in empathy as part of the design thinking process, a 2010s darling of ‘with it’ corporations across industries. Basically, it asked designers to put themselves in their users’ shoes to figure out what those users need.”

“‘Now we’re finding that that’s (BS),’ says Martin. That’s because the practice glosses over the inherent inequity in a system that requires a designer to do the thinking for other people, since the intended user is not designing the product themselves. ‘What’s more important is to go beyond empathy and make sure that the people are creating the work - that are thinking and strategizing - are coming from diverse perspectives.’”

Partnering more fully with end-users could challenge other tropes.

Disrupting the ecosystem by inviting end-users to play a more collaborative role could undercut several of interior design’s more familiar beliefs and practices.

For example, over the past couple of decades, one prevailing thought was that interior designers should strengthen their position within the ecosystem and demonstrate their value to clients by becoming more focused on the values and practices of business. The better interior designers can speak to and demonstrate outcomes that businesses value, the logic goes, the more clients will demand that interior designers have a lead role in the design process.

Also, partnering with end-users could complete the decades-long transition from interior decorating to interior design. It could mean an end to what appears and is lauded in glossy design magazines.

“We’re celebrating the wrong things and our design media perpetuates that.”

Closing the gap - lessons learned from other fields.

As nice as it might be, the field of interior design cannot change its practices or the larger ecosystem just by declaring them changed. There would be too much friction in the form of inertia and conflicting interests. Instead, the field must introduce smaller, more subtle changes that, when broadly adopted across the industry, facilitate the larger shifts and, ideally, make the larger shifts seem inevitable.

Here’s an example; a tad serious but it makes the point. We tend to think that women in the United States won the right to vote in 1920, when the 19th Amendment was ratified. But it didn’t happen quite that way. It happened — as all big changes do — slowly at first, and then all at once. Women won the right to own property. Women won the right to testify in court. Women won the right to divorce abusive husbands. Each win enabled the next. And eventually, there was enough momentum to make a seismic change both possible and seem inevitable. Steps: introducing tools that emphasize the field of interior design could follow a similar path of smaller, but essential designers to lead in new ecosystem; and building public demand for this new version of interior design.

Let's look at these essential steps, one at a time.

New Tools

Too often, we think of tools as devices or implements we use to get a job done. But just as often, our tools are ideas and concepts that frame and explain the job. Those are likely the kind of tools interior design needs to close the gap between its values and practices and to disrupt its ecosystem.

That idea seems simple enough, but it is, in fact, radical. A new ROI would not just be about unseating an essential metric in business, government, and healthcare. It would be disrupting how all actors in the ecosystem think about investments in design, both consciously and unconsciously.

As interior designers are more fully coming to believe, design is not about space. Design is about the people who use and encounter space. Design is not about better space. Design is about better experiences and better lives.

“We need a new ROI.”

“One of the things I find dismaying is that we tend to put all of our energy and focus on the artifacts. And there’s less, a lot less attention on the whole process that led to the outcome, that led to that deliverable.”

People, not space, must be at the center of the calculation. This is particularly true as we prepare people to re-enter the workplace and similar public spaces post pandemic.

All actors in the ecosystem must be challenged to ask: is it worth my organization's time, effort, energy, and resources to create better experiences for people inside and outside my organization? As any MBA will testify, it is always worth the investment to create better experiences.

The Future Vision 2020-21 team asked Zach Anderson, an expert in building social networks and a special guest in the second Future Vision session, what could help bring about a new ROI. He suggested interior design needs to establish industry standards, similar to LEED and WELL, for how deeply engaged end-users are in the design process.

Interior design can't disrupt the ecosystem unless interior designers can measure what they want everyone to care about. Otherwise, there's a vacuum, into which will rush the status quo.

New Education Models

Of course, interior design educators are required to teach for industry as a desired educational outcome and expectation, and that’s unlikely to change anytime soon. But opportunities abound to prepare future designers to close the gap between practice and values, and disrupt the current ecosystem.

The Future Vision team asked Stephanie Pace Marshall, an expert in educational systems and a special guest in the first Future Vision session, what specifically would help prepare future interior designers.

“If every learning experience students had was an experience of what we want them to learn,” she said. In other words, take a page from science education. You don’t just teach students science. You treat students like scientists by making everything an experiment. “They have to experience what we want them to do. They have to be immersed in the language, experience, and manifestations of the belief"

Practically, rather than ask students to design a space, ask students to engage end-users in designing a space. Expect that they develop expertise not just in the space but also in collaborating with the people who will work, heal, learn, or live in it. And prepare students to disrupt the current ecosystem, teach them not only to collaborate with allied professionals, but also how to lead.

Teach them in a way that aligns with interior design’s emerging values, and the new practices should become second nature.

“If I weren’t teaching for industry, I would teach in a totally different way.”

New Narrative

Narrative is an encapsulation of what people believe about you. It isn’t about what you say as much as it is about what others hear, think, and feel. And ultimately, it dictates what power and influence you wield.

For example, for a very long time, the opposite of mental health was defined as crazy, violent, and/or dangerous. People labeled as mentally unwell were ostracized at best and institutionalized at worst. As a result, professionals working in mental health were limited by the narrative, which often defined who they could help and limited their impact. Over time (and with concerted effort), the narrative around mental health began to evolve. Today, it is more common to acknowledge neurodiversity, and redefine the issues and the labels. Presently, the opposite of mental health is more often defined as unhappy and unfulfilled. Sure, there are still some who are ostracized and institutionalized, but the new narrative challenged the old assumptions and threw open the doors so that millions of people could get help.

“The public is badly served by a misunderstanding of what interior designers do.”

This quote makes an important point. It is not that clients are badly served by an outdated story. Nor are interior designers badly served by a faulty narrative. Rather the public itself is denied the degree of assistance to which they are entitled. The stakes may not be quite as high as the mental health narrative, but there are undoubtedly significant costs to perpetuating the wrong interior design narrative.

The answer is to “atomize demand”, said Ethan Decker, a branding expert and a special guest in the third Future Vision session, and Andrew Benedict-Nelson, a strategist for fields and institutions. It is simple. Spread the word to the right audiences. Help end-users understand the full impact of interior design on their experiences and quality of life and they will demand good interior design for their offices, hospitals, schools, and homes.

An example of one such powerful revised narrative strategy can be seen in the United States pharmaceutical industry. For most of modern history, ill people put themselves in the hands of experts (e.g. doctors), who decided what drugs or treatments were appropriate. This is more often than not how interior design works at present. People in offices, hospitals, and schools put themselves in the hands of the building owners, who decide for them what spatial experiences are implemented.

Big Pharma in the United States changed the narrative by advertising directly to end-users. Seemingly our entertainment was sprinkled (and occasionally flooded) with pitches for new drugs and treatments in hopes that individuals would recognize possibilities and begin to take control of their own health decisions by demanding what they want from physicians, hospitals, and clinics. Rather than focus exclusively on the middle-man, Big Pharma communicated directly with prospective patients, thereby empowering them in the process.

Imagine if employees demanded better designed offices, patients demanded better designed hospitals, and students demanded better designed schools, based on the understanding that better design meant true engagement with employees, patients, and students

A closing note from CIDA

Who will design our future?

The foregoing report is both a landing point and a launching point for the interior design profession to discuss and claim agency for a shared future vision. We at CIDA invite our professional colleagues to join us in conversation and initiatives as we strive to continually elevate interior design through practice and higher education quality standards. Our most compelling motivation is the future success of tomorrow's practitioners and empowering them to achieve interior design's full potential.

Endnotes

www.cidq.org/definition-of-interior-design

77,756 interior designers in the US; 17,489 students in CIDA programs. ASID 2021 Outlook and State of Interior Design

The Civically Engaged Reader, ed. A. Davis and E. Lynn, Great Books Foundation, 2006

https://www.fastcompany.com/90552191/4-steps-to-design-a-better-future-after-covid-19

2021 CIDA Board of Directors

Chair Katherine Ankerson, Dean, College of Architecture, University of Nebraska (Lincoln)

Chair-Elect Vincent G. Carter, National Director, Real Property Portfolio, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (Washington, DC)

Secretary-Treasurer Felice Silverman, Principal at Silverman Trykowski Associates (Boston)

Jennifer Busch, Director, Client Partnerships, Eventscape (New York)

Victoria Horobin, Principal, KBH Interior Design (Toronto)

Margaret Portillo, Associate Dean, College of Design, Construction and Planning, University of Florida (Gainesville)

Rachelle Schoessler Lynn, Director of Workplace, Gensler (Minneapolis)

Katherine Setser, Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture and Interior Design, Miami University (Oxford, OH)

Susan Wiggins, Executive Director, Ontario Professional Planners Institute (Toronto)

Executive Director, Holly Mattson, Hon. IDC, Hon. FASID

Acknowledgements

Future Vision 2020-21 Working Group

Jennifer Busch, Director, Client Partnerships, Eventscape (New York)

Jan Johnson, Vice President, Workplace Strategy, Allsteel (Chicago)

Holly Mattson, Executive Director, CIDA (Grand Rapids, MI)

Jacqui McFarland, Senior Associate, Interior Design, Stantec Architecture (Calgary)

Katherine Setser, Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture and Interior Design, Miami University (Oxford, OH)

Felice Silverman, Principal, Silverman Trykowski Associates (Boston)

Future Vision Session 1: What is interior design? (March 2021)

Katherine Ankerson, Dean, College of Architecture, University of Nebraska (Lincoln, NE)

Laura Cole, Assistant Professor of Architectural Studies, University of Missouri (Columbia, MO)

Victoria Horobin, Principal, KBH Interior Design (Toronto)

Jan Johnson, Vice President, Workplace Strategy, Allsteel (Chicago)

Migette Kaup, Professor, College of Human Ecology, Kansas State University (Manhattan, KS)

Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs (Chicago)

Rachelle Schoessler Lynn, Director of Workplace, Resilience Leader, Gensler (Minneapolis)

Holly Mattson, Executive Director, CIDA (Grand Rapids, MI)

Stephania Pace Marshall, Founding President and President Emerita, Illinois Math and Science Academy (Chicago)

Ian Rolston, Founder, Decanthropy (Toronto)

Future Vision Session 2: Who is in our ecosystem? (March 2021)

Zach Anderson, Partner, The Converge Network (Portland)

Julie McHood Barfuss, Project Manager, Salt Lake City Veterans Administration (Salt Lake City)

Jennifer Busch, Director, Client Partnerships, Eventscape (New York)

Vincent G. Carter, National Director, Real Property Portfolio, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (Washington, DC)

Pamela Evans, Principal and Owner, Pique Inc. (Kent, OH)

Jan Johnson, Vice President, Workplace Strategy, Allsteel (Chicago)

Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs (Chicago)

Holly Mattson, Executive Director, CIDA (Grand Rapids, MI)

Margaret Portillo, Associate Dean, College of Design, Construction and Planning, University of Florida (Gainesville)

Felice Silverman, Principal, Silverman Trykowski Associates (Boston)

Kia Weatherspoon, President + Design Advocate, Determined by Design (Washington, DC)

Future Vision Session 3: How does interior design move in the world? (March 2021)

Gabrielle Bullock, Director of Global Diversity, Perkins & Will (Los Angeles)

Ethan Decker, Founder, Applied Brand Science (Boulder, CO)

Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs (Chicago)

Jan Johnson, Vice President, Workplace Strategy, Allsteel (Chicago)

Holly Mattson, Executive Director, CIDA (Grand Rapids, MI)

Jacqui McFarland, Senior Associate, Interior Design, Stantec Architecture (Calgary)

Louis Schump, Creative Director, Gensler (San Francisco)

Katherine Setser, Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture and Interior Design, Miami University (Oxford, OH)

Lisa Waxman, Professor Emerita, Florida State University (Tallahassee, Florida)

Susan Wiggins, Executive Director, Ontario Professional Planners Institute (Toronto)

Future Vision Session 4: What does the future hold for interior design? (March 2021)

Katherine Ankerson, Dean, College of Architecture, University of Nebraska (Lincoln)

William Bouchey, Principal, Director of Design Interiors, HOK Los Angeles (Los Angeles)

Jennifer Busch, Director, Client Partnerships, Eventscape (New York)

Vincent G. Carter, National Director, Real Property Portfolio, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (Washington, DC)

Pamela Evans, Principal and Owner, Pique Inc. (Kent, OH)

Tasoulla Hadjiyanni, Northrop Professor, Interior Design, University of Minnesota (Minneapolis)

Victoria Horobin, Principal, KBH Interior Design (Toronto)

Felice Silverman, Principal, Silverman Trykowski Associates (Boston)

Jan Johnson, Vice President, Workplace Strategy, Allsteel (Chicago)

Migette Kaup, Professor, College of Human Ecology, Kansas State University (Manhattan, KS)

Jeff Leitner, Founder, Unwritten Labs (Chicago)

Rachelle Schoessler Lynn, Director of Workplace, Resilience Leader, Gensler (Minneapolis)

Holly Mattson, Executive Director, CIDA (Grand Rapids, MI)

Margaret Portillo, Associate Dean, College of Design, Construction and Planning, University of Florida (Gainesville)

Katherine Setser, Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture and Interior Design, Miami University (Oxford, OH)

Lisa Kay Solomon, Designer in Residence, Stanford d. school (San Francisco)

Lisa Waxman, Professor Emerita, Florida State University (Tallahassee, Florida)

Susan Wiggins, Executive Director, Ontario Professional Planners Institute (Toronto)

Jim Williamson, Principal, Gensler (Washington, DC)

Survey Respondents (2020)

Taneshia West Albert, Assistant Professor, Interior Design, Auburn University (Normal, IL)

Verda Alexander, Founder / Artist in Residence / Studio O+A (San Francisco)

Donna Assaly, Designer, Assaly Licensed Interior Design Inc., Edmonton, (Alberta)

Julie McHood Barfuss, Project Manager, Salt Lake City Veterans Administration (Salt Lake City)

William Bouchey, Principal, Director of Design Interiors, HOK Los Angeles (Los Angeles)

Bill Browing, Partner, Terrapin Bright Green (Washington, DC)

Gabrielle Bullock, Director of Global Diversity, Perkins & Will (Los Angeles)

Collin Burry, Principal, Gensler (London)

Rosalyn Cama, President, CAMA (New Haven, CN)

Keshia Caplette, Interior Designer, Henry Downing Architects (Saskatoon, Canada)

Joe Capobianco, Design Director, IA Interior Architects (New York City)

Johnson Chou, Principal Johnson Chou Inc., (Toronto, Canada)

Susan Sung Eun Chung, Vice President of Research and Knowledge, American Society of Interior Designers (Washington, DC)

John Cialone, Vice President, Tom Stringer Design Partners (Chicago)

Sarah W. Colandro, Director of Interiors, Buildings + Places, AECOM (Tampa, FL)

Laura Cole, Assistant Professor of Architectural Studies, University of Missouri (Columbia, MO)

Joe Connell, Design Principal, Perkins & Will (Chicago)

Joy Dohr, Professor Emerita, University of Wisconsin (Madison, WI)

Royce Epstein, A&D Design Director, Mohawk Group (Philadelphia)

Annalisa Enrile, Assistant Professor, USC School of Social Work (Los Angeles)

Ellen Fisher, President, Interior Design Educators Council Board of Directors, New York School of Interior Design (New York City)

Thomas Fisher, Director, Minnesota Design Center, University of Minnesota (Minneapolis)

Natalie Flora, Chief Creative Officer, Interior Environments (Detroit)

Micene Fontaine, Executive Director, Design Arts Seminars, Inc. (Monroe, LA)

Lisa Roy-Fulford, SVP Client Strategy, CBRE (Toronto)

Laura Fyles, Strategic Interior Designer, BID, Outloud, (Toronto)

Anna Ruth Gatlin, Assistant Professor, Interior Design, Auburn University (Auburn, AL)

Amanda Guerrier, Interior Designer, ASD|sky (Tampa Bay)

Quintel Gwinn, Principal Designer, Quin Gwinn Studio (Charlotte)

Tasoulla Hadjiyanni, Northrop Professor, Interior Design, University of Minnesota (Minneapolis)

Steve Hart, Principal, HLG Studio (Atlanta)

Todd Heiser, Managing Director, Principal, Gensler (Chicago)

Amy Mattingly Huber, Midwest Director, Business Transition & Move Management, CBRE (Chicago)

Jane Juranek, Associate, Interior Design, IBI Group (Toronto)

Kelsey Keith, Director of Brand Editorial, Herman Miller (New York)

Kerrie Kelly, Creative Director, Kerrie Kelly Design Lab (Sacramento)

Kevin Kelly, Senior Architect, US General Services Administration (Washington, DC)

James Kerrigan, Principal Design and Strategy, Jacobs (Dallas)

Rene King, Assistant Professor, Columbia College (Chicago)

Jennifer M. Kolstad, Global Design Director, Ford Motor Company (Detroit)

Angie Lee, Partner & Design Director – Interiors, FXCollaborative Architects (Chicago)

Lisbeth Linert, Director of Business Development, Clive Daniel Home (Fort Lauderdale)

Jana Macalik, Associate Professor, Environmental Design, OCAD University (Toronto, Canada)

Carl Matthews, Department Head, Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design, University of Arkansas (Fayetteville, AR)

Sally Mills, Principal, Kasian, (Vancouver)

Robert Norwood, Principal, Interior Design Leader, NBBJ (Los Angeles)

Primo Orpilla, Principal & Co-Founder, Studio O+A (San Francisco)

AJ Paron, Executive Vice President, Sandow (Minneapolis)

Tony Purvis, Studio Director, Carson Guest (Atlanta)

Sara Remocker, Senior Interior Designer, Interiors, Dialog (Vancouver)

David J. Roberts, Founder, Nortelus Roberts Group (Tallahassee)

Ian Rolston, Founder, Decanthropist (Toronto)

Joe Rondinelli, Principal, DesignThink Consulting (Boston)

Kay Sargent, Senior Principal|Director of WorkPlace, HOK (Washington, DC)

Tim Schelfe, Vice President + Principal, Britt Design Group (Austin)

Louis Schump, Creative Director, Gensler (San Francisco)

Jason Schupbach, Dean, Westphal College of Media Arts and Design, Drexel University (Philadelphia)

Joey Shimoda, Owner, Shimoda Design Group (Los Angeles)

Stephanie Sickler, Assistant Professor and Foundations Coordinator, Florida State University (Tallahassee)

Georgi-Anna Sizeland, Life Member, Alberta Association of Architects (Toronto)

Elizabeth VonLehe, Design Principal, HDR (New York City)

Kathy Johnston Umbach, Principal, Human Dimensions Licensed Interior Design Services (Edmonton, Alberta)

Ben Waber, Co-Founder and President, Humanyze (Cambridge, MA)

Sascha Wagner, President|CEO, Huntsman Architectural Group (San Francisco)

Kia Weatherspoon, President + Design Advocate, Determined by Design (Washington, DC)

Lois Wellwood Director & Global Interior Practice Leader, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (Los Angeles)

Jim Williamson, Principal, Gensler (Washington, DC)

Milagros Zingoni, Associate Professor, The Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts, Arizona State University (Mesa, AZ)

Additional Interviewees

Sally Augustine, Principal, Design with Science (Chicago)

Jessica Cooper, Chief Commercial Officer, International WELL Building Institute (Washington, D.C.)

Wilhelmina De Castro, Clinical Social Worker/Therapist, Insight (Los Angeles)

Martin Flaherty, President, Pencilbox (Atlanta)

Whitney Austin Gray, Senior Vice President, International WELL Building Institute (Washington, D.C.)

Michael Hirahara, Former Executive with Roku, LinkedIn, and Brocade (San Francisco)

Dallas Salisbury, Former President and CEO of the Employee Benefit Research Institute (Washington, D.C.)

Chris Stulpin, Chief Creative Officer, Mosaic/ Walker Zanger/ Surfaces (Hudson, OH)